Why “QA will catch it” is the most expensive sentence in engineering

At 6:12 PM on a Thursday, a tiny change ships.

It’s the kind of change that feels harmless: a “small refactor,” a “quick fix,” a “one-line tweak.” The PR description is short. The demo works on the developer’s machine. The ticket is already late. Everyone is tired.

Someone comments, almost casually:

“Ship it. QA will catch it.”

It sounds practical. It sounds efficient. It sounds like momentum.

But that sentence is not a plan. It’s a bet.

And it’s one of the most expensive bets engineering teams make—because it pushes the moment of truth to the latest possible stage, where every mistake costs the most.

The 1970 Panic: one null, one assumption, one client escalation

One of the most expensive bugs I’ve seen didn’t involve a massive outage. It involved a date.

We were showing a date on the UI. Everyone reasonably believed the date would always come from the API. That was the contract in our heads: “backend sends a valid date.”

Then the API changed.

For a subset of scenarios, the date started coming as null.

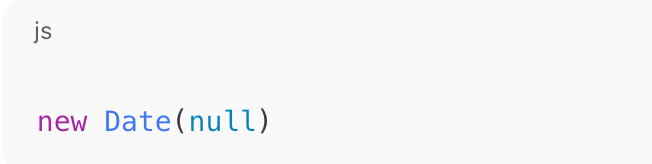

On the UI, our code did something like:

JavaScript doesn’t throw an error here. It doesn’t warn. It quietly converts null into a real-looking date: 01/01/1970 (the Unix epoch).

So the UI didn’t crash. It failed politely.

And that’s exactly what made it dangerous.

A client saw 01/01/1970 and panicked. Not because the product was down—but because the product looked wrong in a way that breaks trust:

- “Is our data corrupted?”

- “Did we lose history?”

- “Why is the system showing 1970?”

It became a production bug reported by a client. The very scenario “QA will catch it” is supposed to prevent.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth:

QA didn’t miss a bug. The system missed a signal.

This wasn’t only a UI problem. It was an assumption problem. A contract problem. A monitoring problem. A rollout problem.

And it’s exactly why “QA will catch it” is expensive: the fix was small. The trust damage wasn’t.

The real problem isn’t bugs. It’s late detection.

Defects don’t become costly because they exist.

They become costly because they survive.

A bug found while you’re coding is cheap:

- You still remember the context.

- The fix is local.

- No one else is blocked.

A bug found after “handoff to QA” costs more:

- Now it’s a ticket in a queue.

- The developer context has evaporated.

- QA has to reverse-engineer intent.

- Re-test cycles stack up.

A bug found by customers costs the most:

- Support and incident response join the chat.

- Stakeholders want updates.

- Engineers context-switch mid-sprint.

- Confidence drops. Releases slow. Fear creeps in.

- Trust takes a hit you can’t “hotfix” away.

When someone says “QA will catch it,” what they’re actually saying is:

“We’re okay discovering defects later—when the cost is highest.”

That’s not quality assurance.

That’s quality gambling.

The hidden lie inside “QA will catch it”

That sentence assumes three things that are almost never true:

- QA has enough time to test everything thoroughly.

- QA can simulate the entire real world—every browser, every data state, every race condition, every integration nuance.

- QA can detect what engineering didn’t make observable.

Some failures don’t show up as errors. They show up as plausible lies—like 01/01/1970.

Those are the worst ones, because they don’t scream. They whisper.

The rare reframe: QA is not a safety net. QA is a strategy.

If you want a system that scales, don’t ask:

“Will QA catch it?”

Ask:

“How do we make defects impossible to ship quietly?”

That shift turns QA into a strategic force:

- designing risk-based coverage,

- shaping acceptance criteria with edge cases,

- ensuring observability exists,

- partnering with engineers on prevention, not cleanup.

The goal isn’t “zero bugs.”

The goal is fast learning with minimal blast radius.

The modern playbook: build quality where bugs are born

Here’s the quality system that replaces hope with design. It’s evergreen—this will matter seven years from now because it’s built on fundamentals: feedback loops, risk reduction, and shared ownership.

1) Shift-left: move validation closer to creation

Shift-left doesn’t mean “test earlier.”

It means detect earlier, using the cheapest feedback loop available.

What shift-left would have done for the 1970 bug

Before coding, the team asks:

- What if the API field is

null? - Missing?

- Empty?

- Wrong format?

That single question would have forced a decision:

- show “Not available”

- show “—”

- or block rendering with a clear message

Instead of letting JavaScript invent a date that looks real.

QA’s role in shift-left (the strategic version)

QA helps create:

- edge-case libraries (nulls, empties, unexpected formats)

- exploratory test charters for risky areas

- definition-of-done rules that include “testable + observable + reversible”

QA becomes the architect of quality, not the janitor of defects.

2) PR checks: quality gates that remove human hope from the process

If shipping relies on “people being careful,” you don’t have a quality system. You have a wish.

A strong PR pipeline is an honesty machine:

- it doesn’t trust intent,

- it trusts repeatable gates.

Minimum PR gate set (works in any era)

- lint + formatting

- unit tests

- component/integration tests for critical flows

- type checks (if applicable)

- static analysis

- dependency vulnerability checks

- build verification

The missing piece: risk-based gating

Not every PR needs the same scrutiny.

But anything that touches:

- dates,

- permissions,

- calculations,

- reporting,

- money,

- migrations,

- caching,

- integrations,

…should be treated as high risk by default.

The one test that would have stopped 1970 forever

Add a unit/component test:

- When the date is

null, UI must show a safe fallback (e.g., “—” / “Not available”). - UI must never show epoch date for that field.

One tiny test turns a future incident into a non-event.

3) Defensive UI: fail safe, not “valid-looking wrong”

Some failures are better loud.

A crash is embarrassing, but a silent lie is expensive.

For date rendering, defensive UI means:

null→ display placeholder- invalid date → display placeholder + log signal

- “impossible values” → treat as suspicious

Because 01/01/1970 is the perfect trap:

- it looks valid,

- it doesn’t trigger errors,

- it scares users.

Your UI should be designed to prevent “real-looking wrong.”

4) Monitoring: when reality speaks, your system should listen

Even great shift-left practices won’t catch everything.

So you need the always-on layer:

Monitoring is QA that never sleeps.

What monitoring would have caught in minutes

- Track metric:

% records with null datefor that field - Log structured event when API returns null for a “critical” date

- Emit a UI telemetry signal if epoch date appears (yes—UI can send quality signals too)

- Alert on spikes after deployment

Then the first “null date spike” triggers an internal alert—before the client email.

This is how mature teams prevent client panic:

Not by never failing,

but by never failing silently.

5) Staged rollouts: reduce blast radius like your reputation depends on it

Because it does.

API changes should rarely go from 0 → 100 instantly.

Staged rollout patterns:

- feature flags (ship dark, enable gradually)

- canary releases (1–5% traffic first)

- ring deployments (internal → beta → full)

- blue/green (fast rollback)

The principle

If you can’t roll back quickly, you don’t have confidence—you have optimism.

Staged rollouts turn optimism into control.

The hidden invoice: what “QA will catch it” really costs

When defects are detected late, you pay in:

- context switching (productivity killer)

- coordination overhead (extra meetings, triage, escalations)

- queue time (rework waits)

- re-testing loops (slow feedback)

- incident tax (on-call stress, fatigue, burnout)

- trust loss (clients + leadership + team confidence)

- release drag (fear slows delivery)

- quality debt (future changes become riskier)

The expensive part isn’t the bug.

It’s the organizational ripple created by late detection.

Replace the sentence. Change the culture.

Next time you hear “QA will catch it,” replace it with:

- “How do we catch this before merge?”

- “What happens if this value is null?”

- “What’s the failure mode?”

- “What’s the monitoring signal if this breaks?”

- “What’s the rollback or flag plan?”

- “What’s the blast radius and how do we shrink it?”

These questions don’t slow teams down.

They prevent teams from slowing down later.

Closing: the day the sentence disappears

There’s a moment in every team’s maturity curve when something changes.

It usually happens after a painful incident—one that drags everyone into a room and makes the air feel heavy.

The team doesn’t just fix the bug.

They fix the system that allowed it.

They add a test that blocks epoch dates.

They update the API contract.

They add monitoring for null spikes.

They stage rollouts for risky changes.

And then, quietly, culture shifts.

Nobody says “QA will catch it” anymore.

Not because QA became unnecessary.

But because QA became something better:

The team’s quality strategy.

And once quality becomes strategy, engineering stops paying the late-detection tax.

Releases become boring.

Confidence becomes routine.

And clients stop panicking over dates from 1970.

#SoftwareEngineering #QualityAssurance #EngineeringManagement #ShiftLeftTesting #Observability #DefectLeakage #EngineeringCulture #QualityEngineering #ReliabilityEngineering #TheGenZTechManager